Did you know that Capital Region Land Conservancy plays an essential role in protecting the James River Park System? In 2009, along with the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation and Enrichmond Foundation as co-holders, CRLC placed 408 acres of the 600 acre park under a conservation easement with the City of Richmond. Not only did this conservation easement permanently protect the park from development, it also means CRLC has a special role in caring for the park’s resources, from historic resources, to land use, to healthy ecology.

Since starting as CRLC Land Conservation Specialist in 2021, I have had my eye on a special project to restore the ecology of a 1-acre meadow adjacent to the JRPS headquarters. This little pocket meadow has been maintained as a grassland since at least 1994, and is in need of a major facelift. Since this grassland is located in a popular urban park, it is a great spot to engage the public about grassland conservation in our region.

Ecology is all the relationships between living things, including plants, animals and humans, and the physical environment. If a park has healthy ecology, it will have many different species of plants, animals, and insects native to that area, living in balance for many years to come.

Why does this grassland need a facelift? Invasive species of plants have been slowly encroaching into the meadow. Birds often carry in invasive plant seeds after feasting on invasive plant fruits and seeds. Invasives can float in during flood events or creep in from nearby neighborhood gardens.

When you think of grasslands, you probably think of the Great Plains to the west. But Virginia ecologists are challenging the assumption that just because an area is forested today, does not mean that it was historically forested. Richmond, Virginia is one of those cities that has lost its historic grassland habitat. If we are missing out on grassland habitat native to this area, it means our ecology is not as healthy and stable as it should be.

“Most Americans are unaware that cities such as Charlotte, Chattanooga, Huntsville, Montgomery, Nashville, Raleigh-Durham, Richmond, and Tallahassee, among others, are as much "grassland cities" as Austin, Fort Worth, and Tulsa.”

Southeastern Grasslands Initiative

Southeastern Grasslands Initiative (SGI), an organization that works to conserve, restore, and promote native grasslands of all types throughout the Southeast, has been trying to bring awareness to grassland habitats which are recognized as some of the most endangered landscapes in the South. According to their website, “Most Americans are unaware that cities such as Charlotte, Chattanooga, Huntsville, Montgomery, Nashville, Raleigh-Durham, Richmond, and Tallahassee, among others, are as much “grassland cities” as Austin, Fort Worth, and Tulsa. These southern cities were colonized early because the native grasslands, prairies, and savannas were hospitable environments, often with deep, fertile soils, so they were gone before the camera was invented…before they could be described. Much of the original landscape—so important to indigenous people and the earliest settlers—has been lost.”

But all is not lost! My goal for this meadow at the JRPS headquarters is to restore it to help bring awareness of these important landscapes that historically were very abundant in the Richmond area. With that restoration, this ecosystem will provide important benefits including improving water quality, carbon storage, wildlife and pollinator habitat.

Restoring a meadow does not happen overnight. It’s easy to want to jump in and get your hands dirty right away when a project like this comes along. Here at CRLC, we believe that the first step to a successful ecological restoration project is to conduct research on historical uses of the property and find out what is already there. This requires vegetation surveys to be conducted 2-3 times during the growing season to get an understanding of what native and invasive species live on the property, which can vary significantly during different times of the year. This also gives us an idea about which species might come up following a disturbance in the soil seed bank The seed bank is the natural storage of seeds, often dormant for long periods of time, within the soil. The soil seed bank might be full of really cool native plants just waiting for a disturbance, like fire or a flood, to make space for them to grow, or could be full of some nasty non-native & introduced species, such as invasive plants.

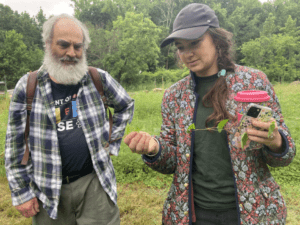

Our first survey was conducted in late May this year. In roughly an hour, we identified 45 species, of which 6 were species that were listed as invasive. Some of these invasives you might know: Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), Ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea), Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), and Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora).

We also found 9 species that are considered “introduced,” that are non-native, non-invasive species. A total of 30 native species were identified! Most exciting of which for me was the Eastern Gamma Grass (Tripsacum dactyloides), two species of goldenrod (Tall goldenrod (Solidago altissima) and giant goldenrod (Solidago gigantea), Indian Hemp (Apocynum cannabinum), and early wild rye (Elymus macgregorii).

We were excited to find that almost half of the project area is currently vegetated in desirable native plants (mostly consisting of the aforementioned species). Not only will JRPS staff not have to start from scratch while working on this project, but restoration will be much simpler: some light invasive plant management, then planting and seeding of native species in following years.

This year we have two more plant surveys to go in late summer & late fall. Following a year of data collection & research, we will map out areas that need a complete overhaul then plant with local ecotype native plants. “Local ecotype” means that these native plant seeds were collected from seed right here in the Richmond, Virginia area. The work ahead will return native plants home to this meadow!

Keep Learning and Get Involved!

You’ll hear more about this project as we get into the weeds, including volunteer opportunities to help us plant out native plants at this meadow.

Volunteer: Are you interested in learning more about plant identification on public lands with CRLC? Sign up to join our volunteer list here!

Identify Plants: Two of my favorite tools for surveying and identifying plants are the Seek app by inaturalist and the Flora of Virginia App. Seek is a free app created by the makers of iNaturalist that uses your smartphone’s camera to identify plants, somewhat accurately. The Flora of Virginia app is not free ($20), but is extremely useful in verifying the plants identified by Seek (which was fairly accurate during our work at Reedy Creek this May) and help you with the identification of plants that Seek cannot identify. With built in information on natural distribution of plants, bloom times, and taxonomic keys, the Flora of Virginia App is worth every penny!

Learn more about grasslands: For additional reading on grasslands in the south, please check out Forgotten Grasslands of the South and the Southeastern Grasslands Initiative.

Ashley Moulton

CRLC Land Conservation Specialist